- Home

- Pyotyr Kurtinski

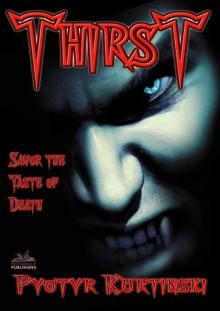

Thirst Page 4

Thirst Read online

Page 4

But it was time to be serious; he had a problem that just would not go away. Maggie Connors! But how serious was the situation? Not so serious, he supposed. What could she do with the picture? Give it to Click magazine, the photography monthly, or some other magazine, with a story about her encounter with a vampire in the Bronx Zoo. The awful thing was, her work appeared in most of the popular magazines. How awful it would be to see his picture on the cover of People or Time. Even worse would be to see himself on page one of the National Inquirer, sharing space with Elvis and Roseanne stories. The possibility made him want to vomit.

There was no way out of it: He would have to find the pictures and destroy them—and kill Maggie Connors at the same time. But he wouldn’t just kill her, of course. The worst death in the world was what he had in mind for her, and he wondered what that might be. There were so many ways. He wanted her to die screaming or to die without the ability to scream, the power to express her pain. Could she still scream if he cut out her tongue, but not her vocal cords?

Van Diemen swallowed two Ritalin tablets to counteract the drowsiness he felt creeping over him. A glass of vodka helped to get them down, and he lay back in his chair, waiting for the drug to take effect. Ritalin really called a halt to his maudlin thoughts. Feeling ever so much better, he began to reconsider the Maggie Connors problem, if problem it was. All right, suppose his picture did appear on the cover of some rag or was given a prominent place inside. Why should he be concerned? Not too many people knew what he looked like, besides his five mistresses and, of course, his lawyer. It had been necessary to meet Bradford Wilcox in person when the lawyer had taken over the Van Diemen account after his father’s death. Until then Van Diemen’s new lawyer had been no more than a voice on the telephone, and that wouldn’t do; he needed to see the man up close, get the feel of him, decide if he could be relied on. There had been too much at stake to take Bradford C. Wilcox on trust.

Very well then, six people could identify Van Diemen if they saw his picture. Maggie Connors made seven. Sandor and Drina didn’t count. Actually, when Van Diemen thought about it, the only one who knew his name and knew where he lived was Wilcox, and he wouldn’t say a word. On the other hand, Wilcox would surely become very nervous if and when he discovered that his largest client was a vampire. Up till this point, his lawyer seemed to regard him, he hoped, as a multimillionaire eccentric, and that was fine. So many rich people were eccentric.

The mild ones ran for President or funded model communities for cats; the real nuts tried to get on welfare or protested cruelty to plants. But if the picture and a story did appear in some lightweight magazine, would he even see it? Probably not. The Times, Law Journal, Wall Street Journal, and Greenwich Bugle would be the newspapers he read. For magazines, Wilcox probably choose Time, Newsweek, Yachting, Golf, and Money. Van Diemen knew he was guessing, but he thought he knew his man. He was fairly sure Wilcox didn’t read newspapers or magazines that were likely to run vampire stories. But Time might pick up the story and give it an inch or two as a joke. Even the Times might do it. The Good Gray Lady of West Forty-third Street was getting jazzier all the time.

In the end, after going over all the possibilities, Van Diemen knew he had to find the photographs and kill Maggie Connors. There were no two ways about it. He had to kill Maggie Connor any way he could, and if that meant letting her off with a quick death, then so be it. He got up and took the Manhattan telephone directory from a bookshelf and looked under Connors. There was a Margaret Connor in the book, but she was a doctor with an address on West Eighty-sixth Street. No Maggie. Van Diemen called Information, but they had no listing for a Maggie Connors in any of New York’s five boroughs. Van Diemen called Click magazine and got an answering machine. But the magazine was a waste of time: They wouldn’t give out that kind of information, no matter what sort of yam he tried to spin. It would be the same with the Photographers Guild, he was fairly sure. They would ask him to leave a message or write in care of the office.

Who’s Who in America was a possibility, but Van Diemen didn’t have a copy and the public library was closed. All he could do was call in the morning. That would interfere with his daytime rest, the hours when he dreamed his vampire dreams. But there was no help for it; it had to be done. He couldn’t ask Sandor or Drina to make the call; their English was poor. They were all right with simple calls, like the time they’d had to call the exterminator because an army of rats had invaded the castle. Van Diemen liked rats, but not when they threatened to chew up his library.

He looked up when the wood-encased clock gonged out the hour. Two o’clock and he hadn’t written a line all night. He damned Maggie Connors for upsetting him, and he damned himself for not following what was to be his routine. It was time to get serious: no more flitting about in that damned zoo, no more snatching women off crowded streets. That was kid stuff, Van Diemen the daredevil showing off, and it could get him into some kind of trouble. He had, in the legal sense, committed 75,000 murders over the years, but long-forgotten killings were no cause for concern. His more recent killings were. Some were less than perfectly done. Some of his victims had described him to the police or to ambulance crews before they had died. A few had survived; he’d read about them in the newspapers. It had been amusing to read their descriptions—tall, distinguished, pale, fat, thin, foreign-looking. But it wasn’t amusing now. The damned photographer had his picture!

But he was safe enough if he stayed close to home, went out once a night for a safe kill, then returned to his cozy castle to write until the gray dawn. What was to connect him with random killings committed in such far-apart places as the Grand Concourse, Queens Village, or Christopher Street? What was to connect the scholarly recluse of northern Riverdale, the dedicated writer, to such bloodshed?

And writing was what he should be doing now, and by beggar’s lice, he would. Let tomorrow’s problems take care of themselves; tonight he would be like an ancient Irish monk hunched over the Book of Kells. He drew his thin pile of manuscript pages close, to him and read what he had written before morning light had disturbed him. Then he dipped his pen into the inkwell and wrote:

I returned to Amsterdam a vampire, and there I was greeted by an ultimatum: Go to America or get out. I was only too glad to leave my father and dreary old Amsterdam, with its tiresome rectitude and stinking canals. My father paid my passage to New York. It was the last money he would ever spend on me, he said. Nonetheless, the fare to New York was the least of my worries. How was I to survive the long voyage without feeding once every day? It is possible to survive on less, but such deprivation can be dehabilitating in the extreme. A vampire must have rich red blood; storing the blood of victims in flasks will not work. So I must confess I was in a state of great agitation when I boarded the bad ship Batavia, a decrepit hulk, one spring evening in 1799. Luckily for me, as it turned out, the Batavia was an emigrant ship—a coffin ship, as such ships came to known during the Irish Famine. Below decks, in steerage, it was crammed with the wretched of the earth, the sweepings of Europe, half starved, virtually nameless, of importance to nothing and no one, even themselves.

I fed on them during the crossing. Their families and friends cried out at their disappearance, but no one else did. Yes, I had to take chances, for what else could I do? There was a dangerous time at mid-crossing, when some of their number threatened to take over the ship as the only way to protect themselves. This uprising was quelled only by the firm resolution of the captain and his officers, and for too long, there was a stalemate. The rebellious steerage passengers held the captain and crew at bay with broken bottles and sharpened sticks while the captain ordered the odd volley of musket-balls when he wasn’t shouting through a megaphone.

Naturally, I did not dare to venture below decks, for the maddened creatures there would have torn me to pieces. Before the pitiful uprising, it had been easy enough to descend into steerage, always in the dead of night, bringing with me a little food or a bottle of cheap rum. There i

n darkness and never-ending tumult, I found no great difficulty in feeding night after night. All this ended with the uprising, and I was forced to drink the blood of the rats that infested the ship. Yes, a vampire can subsist on the blood of any warm-blooded animal, but it is no substitute for the blood of humans. Thus, I was in a greatly weakened condition when the Batavia docked in New York. Oh, how glad I was to leave my dirty little cabin and that stinking ship.

My worldly possessions consisted of a small valise containing some clothes and a sealed jar filled with dry red earth from the grave of Countess Erzsebet of Bathory. Late at night though it was, the grogshops and steaming oyster bars of South Street were thronged with sailors, dockers, robbers, prostitutes, and all the other creatures who live by night. But I had no need of food or beverage. I needed hot, spurting blood. It turned out to be the blood of a flaxen-haired prostitute, not really so old but ravaged beyond repair. She named a price and I followed her into a rubbish-strewn alley. There I seized her before she could utter another word. Even now, two centuries later, I remember clearly how greedily I drank her blood, how delicious the taste was, how I felt my strength returning even before I released her body.

That same night, reinvigorated in mind and body, I set out for Jacobus Van Diemens Hudson River estate. I could have taken one of the passenger boats that traveled between New York and Albany, but after the crossing, I’d have no more of boats. Spring had turned to summer when I landed in New York, and my journey up the Hudson, on foot, was altogether delightful By day, I rested in some dark place: a cave, a ruined barn, the deepest part of deep woods. Feeding was no problem. In those days, the countryside was thronged with itinerant laborers drifting from one job to another. Usually they slept in the fields, in haylofts, or anywhere they could find when the weather was fine, and that summer, in my memory, was finest of all, in a way the happiest time of my life.

I arrived at my destination to find Jacobus Van Diemen dead and buried, his entire fortune willed to me on his deathbed. Everything was mine: house, lands, ships, a private bank, New York City property, and a little more than a million dollars in cash. Oh, how the other Van Diemens hated me, this shabby interloper from Amsterdam. But there was nothing they could do to break the will, though they tried hard enough in the courts. Old Jacobus had seen to that. Arrogant, willful, and eccentric though he was, no one had ever called him feebleminded. His will had been drawn up by the finest lawyer in the state and witnessed by a bishop and a United States senator:

I was, in the slang of a much later time, sitting pretty. As I have written earlier in this narrative, a vampire s basic nature does not change simply because he becomes one of the undead. In my former life I had greatly appreciated the fine things of life, though I had little money to indulge myself. Still, I had longed for fine and beautiful things: books, paintings, elegant houses, anything my young, sensitive mind was drawn to. And now I had the money and time beyond mere life to possess anything my heart desired.

But I was a prudent vampire for all that. Not for me was the wild spending that so often ruins a young man suddenly come into money. First I must have a secure place to live; without that I would remain always in some danger. If danger isn’t quite the right word, its close enough. I wanted most of all to put down roots, to find a place where I would be safe for as long as the world remained in existence. When I did so, everything else would follow: the art collection, the library of rare books, the cellar filled with superb wines.

I wanted to build a castle as my permanent home. At first, I was tempted to commission a replica of Prince Dracul’s once magnificent and now ruined castle at Tirgoviste. Finally, after much thought, I decided against it. Why draw attention to myself? Prince Dracul’s castle was so Eastern looking, almost Oriental, with its slender towers and delicate ornamental stonework. Some architect or historian was certain to identify my castle as being modeled on the original edifice. And that would not do. Yet I must have a castle, an English castle as it turned out, very much like one I’d seen in Oxfordshire during my student days. It was an excellent choice and I’ve never regretted it.

I commissioned New York’s most celebrated architect and he went to England to study records relating to the ancient structure. While he was away I sold all my property through a law firm specializing in such matters. I rid myself of anything that might prove to be an encumbrance, keeping only Jacobus Van Diemens house and lands on the Hudson. My castle could not be built in less than a year, the architect informed me, and in the meantime, I would need a place to live.

The sale of my property realized an enormous amount of money, which I deposited in the New York branch of the Bank of England, then the soundest bank in the world. I had so much money that I could have purchased the Oxfordshire castle and brought it over stone by stone, as that fellow Hearst did later with some of his acquisitions, but I never gave such a scheme serious consideration.

But my reader may wonder if building a full-scale English castle in a modem republic would not result in a great deal of newspaper publicity, perhaps even ridicule. Not at all. Castles were far from unknown in Colonial America, and while many were shabby imitations, some were quite grand, if not quite authentic. For my part, I was determined that my castle would be nothing at all like the sham castles built along the Hudson by vulgar millionaires in the years before and after the American Civil War.

Anyway, my architect finally returned and the building commenced. I had chosen Riverdale as the site because of its proximity to New York City. / had passed through the district on my first journey upriver to Jacobus Van Diemen’s estate. It was completely rural then, yet close to the city, and I anticipated many adventures in the rapidly expanding region. It was all right to feed on itinerant laborers when there was little else available, but there would come a time when I needed more variety, more excitement

Land in Riverdale was dirt cheap then, and I got my forty acres for a song. This was in the fall of 1800, and my architect assured me that my castle would be complete by Christmas of 1801. Meanwhile, I was to live at the old manor house on the great river. And a lovely house it was, many gabled in the Dutch style and built of the small yellow bricks brought over from Holland in the early days of the province. Peter Stuyvesant held the reins of government then, but the Van Diemens were no less great in their way. By great I don’t mean greatness in any of the arts. My family’s genius was for commerce and the law. After I had beaten my relatives in the courts, some of them tried to come to see me. They sent letters when I refused their overtures, desperately trying to mend the fences they had broken themselves. But I wanted nothing to do with them, not from any lasting rancor, but from a strong desire to live an untroubled life free of money talk and the petty quarrels of greedy men.

I visited Riverdale a number of times while my castle was in various stages of construction. It wasn’t that I didn’t have the fullest confidence in my architect. He was a man of integrity and renown who didn’t try to dazzle me with the technical details professional men are so fond of. The work was going on apace and I had no cause for complaint. I would have come to Riverdale more often if I had possessed the power of bat flight, but I didn’t master that feat for several years. However, I was already studying the possibility of harnessing my willpower to transform myself into a giant bat. I had to make my way to Riverdale in the shape of a mortal.

Here I must again refute the long-held belief that a vampire cannot go out in daylight. It simply isn’t true, though a vampire must be careful not to expose himself to the sun’s rays for too long. The sun’s rays are dangerous, and they can be fatal. When a vampire ventures out during the daylight hours, he must go well muffled, well shaded by a broad brimmed hat and the largest smoked glasses he can obtain. In modem times he will have the added protection of a sun block lotion, but even then, he must be mindful of the danger the sun presents. Best of all, of course, is to go out on overcast days, and that was what I tried to do during my visits to Riverdale.

I remained

fascinated as the work on my castle progressed. I never tired of watching the workmen and artisans—stonemasons, marble cutters, woodworkers—at their labors. All had been brought over from Europe. They spoke little or no English, they were paid well, and they were sent back when the work was complete. They carried back some of my secrets, but they were generally ignorant men; so I had little to fear from them. To be practical, I couldn’t kill all of them. I did kill the architect though I felt some regret at having to do so. But he was an Englishman who had long lived in America. He was something of a favorite in New York’s social circles, and he knew too much about me. I’m not saying he would have talked, but he might have, perhaps in old age when men are inclined to ramble on about the past. I couldn’t take the risk.

I killed him on the day I took possession of my castle. We had gone over my new residence from dungeon to tower, and from the tower, I pushed him to his death on the cobblestones far below. No, I didn’t make him a victim or feed on him—nothing like that, though he was a jolly, portly fellow fairly brimming with rich blood. On the day he died, we had drunk several congratulatory toasts—brandy and water for him, cold champagne for me—and he was in a merry mood by the time we ascended to the tower. A swift push and it was all over.

There was little investigation into his death. After all, he was known to drink a little too much, especially at the conclusion of some outstanding project. The police and his society friends regarded his demise as a tragic accident, and that was the end of the unpleasant matter. I was safe and so were the secrets of my castle. It still amuses me to look back at the newspaper stories that described what came to be known as Van Diemen’s folly. Mercifully, the notoriety didn’t last very long. Follies far greater than mine, if folly it was, were being built by very rich men, and when a former slave trader commissioned an enormous house to be modeled after the Great Pyramid, my castle was quickly forgotten. I was thought to be somewhat eccentric, nothing more than that. In America, as elsewhere, a rich man of peculiar tastes is described as eccentric, while a man with far less money is simply mad.

Thirst

Thirst